Intro to the S.A.I.D. Principle

INTRODUCTION

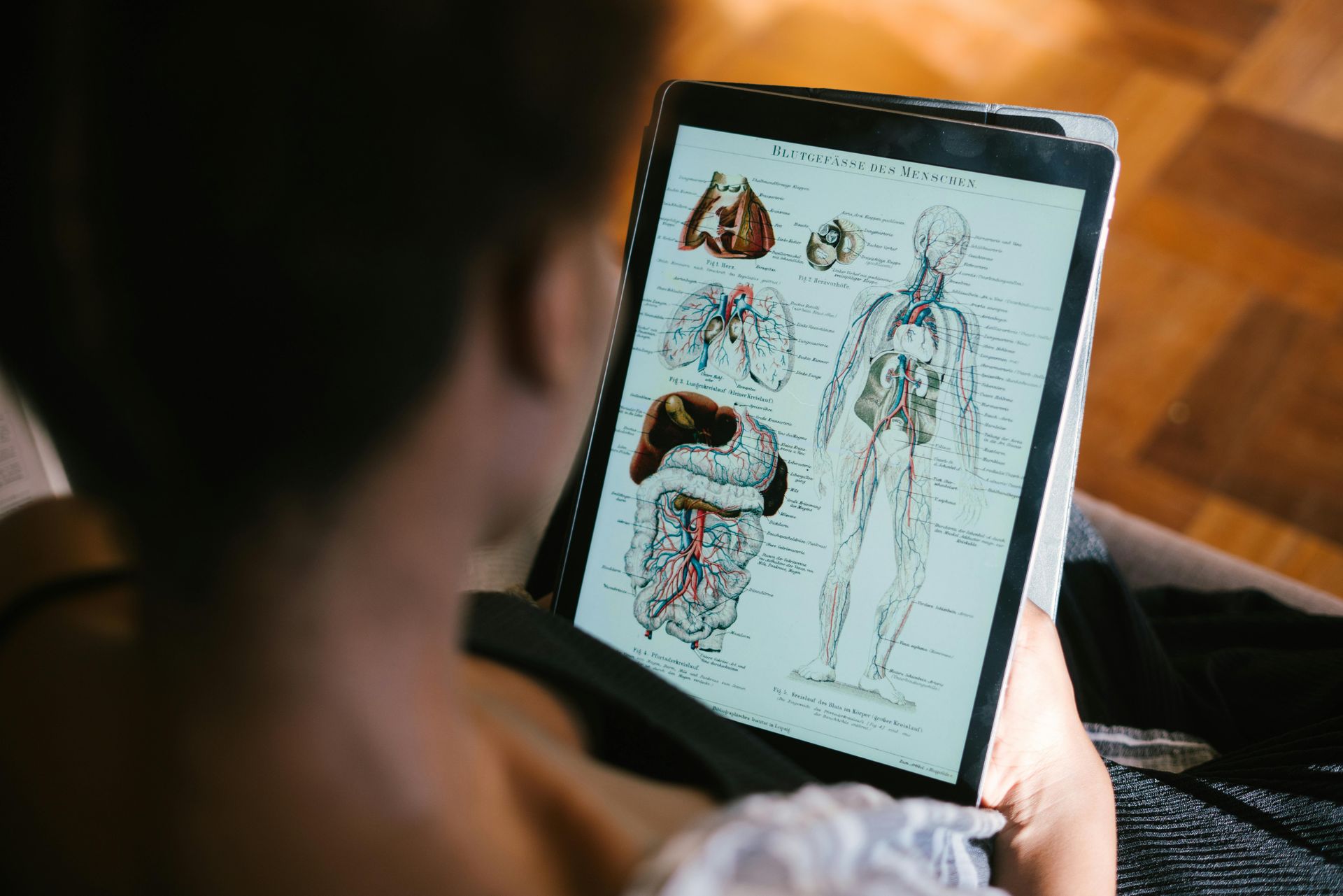

Your body is amazing at adapting to what you do regularly. This is called the SAID principle, which stands for Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands. In simple terms, it means your body changes based on how you use it or in a way, don’t use it.

For example, people who spend a lot of time on their phones often develop a hunched posture because their bodies adapt to that position. Their hamstrings get longer, hip flexors get shorter, and their chest muscles tighten up. On the other hand, people who lift heavy weights muscles get stronger. Those who do a lot of steady state, slow cardio exercise improve their ability to utilize oxygen by improving uptake at the cell level and increase their heart and lung function.

The SAID principle is important in exercise science. It helps professionals and their athletes create specified workout plans. By understanding this principle, coaches can make sure training routines match their population(s) fitness & performance goals.

Whether a person wants to build muscle, improve endurance, or just stay healthy, using the SAID principle will ensure that the training plan will result in the desire adaptations.

This article will provide an introduction into the SAID principle. Future articles will expand on incorporating the SAID principle into various training programs.

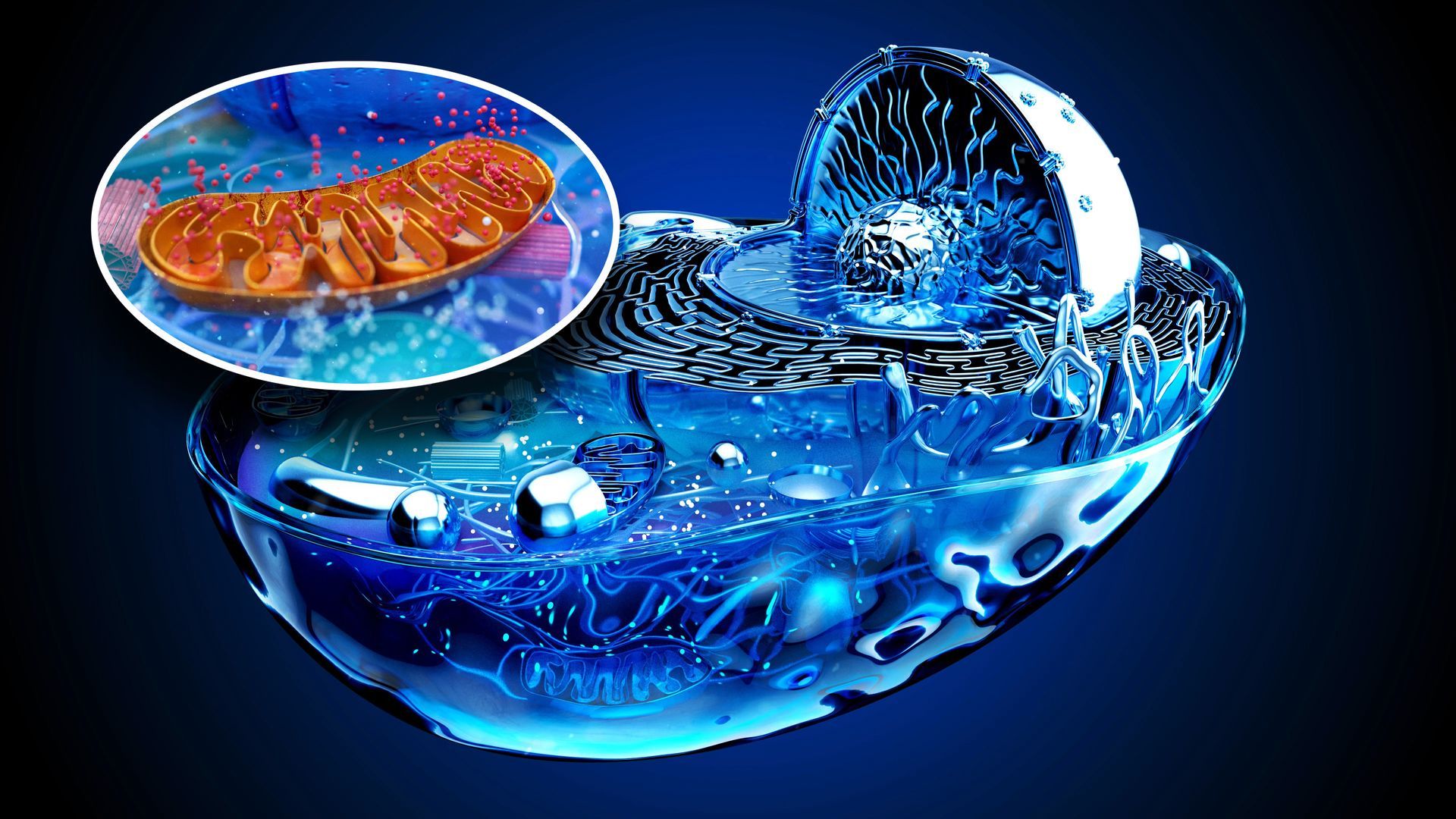

AEROBIC TRAINING AND THE SAID PRINCIPLE

The SAID principle in aerobic training leads to specific cardiovascular and muscular adaptations. Regular aerobic exercise improves heart function, increases stroke volume, and enhances oxygen delivery to muscles. It also develops slow-twitch muscle fibers, increases capillary density at the tissues, boosts mitochondrial density, improves fat metabolism, and enhances neuromuscular efficiency. The body adapts to utilize energy systems specific to the duration and intensity of training. For example, a person that only trains at or near lactate threshold will have neither VO2max or aerobic capacity, but will increase their bodies ability to utilize and clear lactate.

To apply the SAID principle effectively, match training intensity and duration to your goals, progressively increase training volume, and incorporate sport-specific movements.

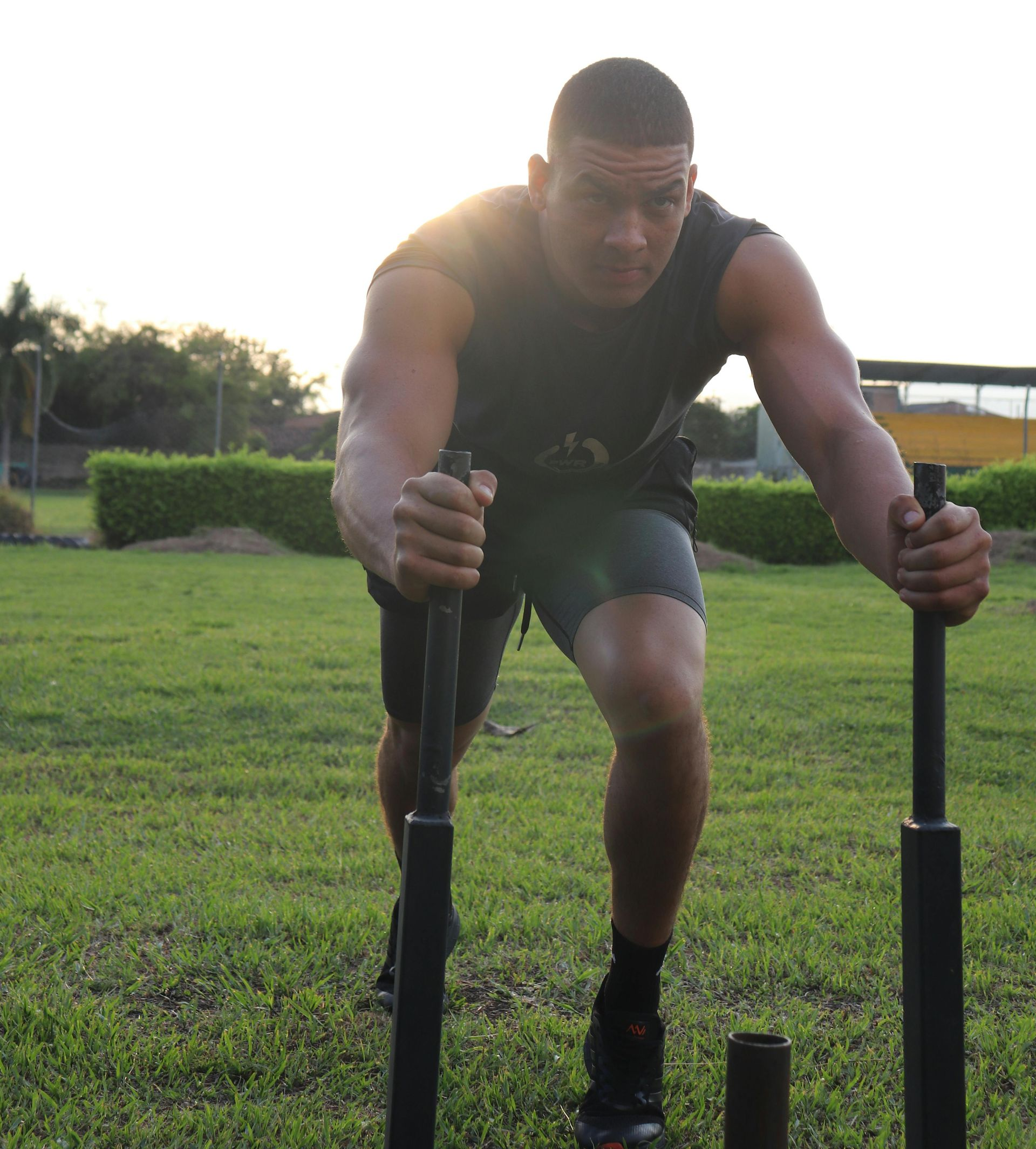

STRENGTH TRAINING AND THE SAID PRINCIPLE

In strength training, the SAID principle is evident through neuromuscular adaptations, and movement pattern specificity. Specific strength exercises improve neural recruitment and synchronization of muscle fibers. Different loading schemes target fast-twitch or slow-twitch muscle fibers, and strength gains are most pronounced in the specific movements trained. To apply this principle, choose exercises that mimic your sport or daily activities, vary rep ranges and loading schemes, and progressively overload exercises to continue challenging the muscles and nervous system.

HYPERTROPHY TRAINING AND THE SAID PRINCIPLE

For muscle growth, the SAID principle guides adaptations in muscle fiber hypertrophy and metabolism. Specific training protocols lead to increases in muscle fiber size, and the body adapts to handle increased workload and nutrient demands for muscle growth. To apply this principle in hypertrophy training, focus on exercises targeting specific muscle groups, utilize appropriate rep ranges and time under tension, and progressively increase volume and intensity to continue stimulating muscle growth.

SPORT-SPECIFIC TRAINING AND THE SAID PRINCIPLE

The SAID principle is crucial in sport-specific training, emphasizing movement pattern specificity and skill acquisition. Training should replicate the exact movements and energy systems used in the sport, and repeated practice of sport-specific skills leads to neural adaptations that improve performance. To apply this principle, analyze the demands of your sport, design training programs that mimic those demands, incorporate drills replicating game scenarios, and progressively increase the complexity and intensity of sport-specific exercises.

THE SAID PRINCIPLE & MALADAPTATIONS FROM A SEDENTARY LIFESTYLE

While the SAID principle is often discussed in the context of positive adaptations from exercise, it's equally applicable to understanding negative adaptations or maladaptations that occur from prolonged sedentary behaviors, such as sitting.

For example, take a person that has an 8 hour desk job with a 45-60 minute commute. They workout for 45 minutes in the evening, commuting 15 minutes to and from the gym where their cool off period is mostly the way home from the gym.

Below is the standard adaptations expected with a person that fits this criteria.

POSTURAL CHANGES

Prolonged sitting imposes specific demands on the body, leading to adaptations that can be detrimental to overall musculoskeletal health. The seated position keeps the hip flexors in a shortened state, which can result in adaptive shortening over time. This constant flexed position at the hips can lead to tightness and reduced flexibility in these muscles. Additionally, the glutes and hamstrings remain largely inactive during sitting, potentially leading to weakness and reduced activation in these important muscle groups [1]. The tendency to hunch forward while sitting can also have negative consequences, often resulting in a rounded upper back. This posture can lead to adaptive shortening of chest muscles and a corresponding lengthening of upper back muscles, contributing to poor posture and potential discomfort or pain in the upper body. These adaptations highlight the importance of regular movement and postural awareness to counteract the effects of prolonged sitting [1].

MUSCULAR IMBALANCES

The SAID principle (Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands) provides insight into how prolonged sitting can lead to significant postural changes and muscular imbalances. As the body adapts to the demands of extended periods in a seated position, it develops specific muscular patterns that can have far-reaching effects on posture and overall musculoskeletal health. For instance, the combination of tight pectoral muscles and weak upper back muscles often results in rounded shoulders and a forward head posture, altering the natural alignment of the upper body. Similarly, the shortening of hip flexors, coupled with the weakening of gluteal muscles due to inactivity, can significantly impact pelvic positioning. This imbalance can potentially contribute to lower back pain and other related issues. These adaptations underscore the importance of understanding the SAID principle in the context of sedentary behaviors and highlight the need for targeted interventions to counteract these negative postural changes [1].

METABOLIC ADAPTATIONS

Prolonged sitting not only affects our musculoskeletal system but also imposes significant metabolic demands, or more accurately, a lack thereof, on our bodies. The extended periods of inactivity, particularly in the large leg muscles, can lead to decreased insulin sensitivity and an increase in fat concentration in the blood. This reduction in muscle activity means that our bodies are not actively using energy as they would during movement or standing. As a result, the body begins to adapt to this low-energy state, potentially leading to reduced metabolic efficiency over time. These adaptations can have far-reaching consequences for our overall health, contributing to issues such as weight gain, increased risk of type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular problems. Understanding these metabolic adaptations underscores the importance of regular movement and activity breaks, even in environments that require extended periods of sitting.

COUNTERACTING SEDENTARY ADAPTATIONS

Understanding these maladaptations through the lens of the SAID principle can help in designing effective strategies to counteract them:

1. Regular movement breaks: Interrupting long periods of sitting with short bouts of activity can help prevent these adaptations[1]. You can go for a short walk every 45 minutes or better yet, perform a one minute bout of high intensity exercise, such as burpees or jumping jacks.

2. Targeted exercises: Incorporating exercises that specifically address the muscles affected by prolonged sitting (e.g., hip flexor stretches, glute strengthening exercises) can help reverse these adaptations[1].

3. Ergonomic adjustments: Modifying the work environment to encourage better posture and more movement throughout the day can help impose different demands on the body[1]. Try to incorporate a stand up desk or choose to stand when possible.

SUMMARY

The SAID (Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands) principle is a fundamental concept in exercise science and physiology that explains how the human body adapts to the stresses placed upon it. This principle applies to both positive adaptations from exercise and negative adaptations from sedentary behavior. In the context of exercise, the SAID principle guides the development of targeted training programs. For aerobic training, it leads to cardiovascular improvements, enhanced oxygen delivery, and increased muscular endurance. In strength training, it results in neuromuscular adaptations, changes in muscle fiber types, and movement-specific strength gains. Hypertrophy training focuses on muscle growth through specific protocols that increase muscle fiber size and metabolic efficiency. Additionally, sport-specific training emphasizes replicating exact movements and energy systems used in particular sports to improve performance.

However, the SAID principle also explains maladaptations that occur due to prolonged sedentary behavior. For instance, sitting for extended periods can lead to postural changes such as shortened hip flexors, weakened glutes and hamstrings, and rounded upper backs. These adaptations contribute to muscular imbalances, including tight pectorals and weak upper back muscles, which can alter pelvic positioning. Furthermore, sedentary behavior can negatively impact metabolic health by decreasing insulin sensitivity and reducing overall metabolic efficiency.

To counteract these negative adaptations, it is crucial to incorporate regular movement breaks and targeted exercises that address the specific demands of prolonged sitting. Understanding and applying the SAID principle is essential for designing effective exercise programs, improving athletic performance, and maintaining overall health in our increasingly sedentary society.

SOURCES

[1] https://www.ptpioneer.com/personal-training/certifications/study/said-principle/

[3] https://www.bettermovement.org/blog/2009/0110111

[4] https://www.simplesolutionsfitness.com/said-principle

[5] https://www.freeletics.com/en/blog/posts/said-training-principle/

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SAID_principle

[7] https://www.mdpi.com/2411-5142/7/4/76

[8] https://oshwiki.osha.europa.eu/en/themes/musculoskeletal-disorders-and-prolonged-static-sitting

[9] https://safunctionalfitness.com/said-principle/

[10] https://www.freeletics.com/en/blog/posts/said-training-principle/